Feb 12, 2025

Articles

Feb 12, 2025

Articles

Feb 12, 2025

Articles

21-CFR Part 211 - Guidelines for Pharmaceuticals

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

Martín Ramírez

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most highly regulated sectors worldwide, and for good reason: any lapse in quality can directly impact patient health.

In the United States, 21 CFR Part 211 sits at the core of the FDA’s current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) requirements for finished pharmaceuticals.

These regulations can seem a bit much, but they exist to protect consumers by ensuring products are consistently safe, pure, and potent.

The Historical Underpinning: Why Part 211 Exists

Modern pharmaceutical regulations have roots dating back to early 20th-century reforms when unsafe or fraudulent medicines prompted lawmakers to demand higher standards of manufacturing and distribution.

Over time, repeated incidents – from tainted cough syrups to eye drops contamination – refined the scope of these rules.

In the late 70s, the FDA finalized 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211, which are core CGMP regulations. Together, they outline the responsibilities of drug manufacturers to ensure drug purity, potency, and consistency.

Part 210 provides overarching definitions and general provisions.

Part 211 builds on that foundation by specifying requirements for everything from personnel qualifications to detailed recordkeeping.

Purpose of 21 CFR Part 211

Under 21 CFR § 211.1, the FDA clarifies that Part 211 contains the “minimum current good manufacturing practice” (CGMP) for preparing drug products (excluding positron emission tomography (PET) drugs) for both humans and animals.

The phrase “minimum” is important: many companies opt for even stricter standards based on their risk assessments.

The main goal of 21 CFR Part 211 is to guarantee that every drug product meets its intended specifications and is safe for consumers.

By establishing detailed guidelines for facilities, equipment, processes, training, and documentation, Part 211 helps manufacturers:

Prevent errors and inconsistencies.

Maintain product quality and safety from the earliest production stages to final distribution.

Protect patients from ineffective or contaminated medications.

Unlike less-regulated sectors, drug manufacturing requires rigorous oversight of everything (from container closures to personnel qualifications) because patient safety is on the line.

While cosmetics regulations, such as Part 701 for labeling, have their own standards, Part 211 has more stringent requirements because pharmaceutical products pose a higher risk to consumer safety.

Additional considerations:

Part 211 interacts with other FDA regulations.

For drugs that are also biologics (e.g., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies), or human cells and tissues regulated under parts 600 through 680 and part 1271, those specialized rules “supplement and do not supersede” Part 211.

In other words, if there’s a conflict, the more specific or stricter requirement prevails (§ 211.1(b)).

Potential exemptions for certain OTC products that are also foods might apply under part 110, 117, or 113–129 if the product is “ordinarily marketed and consumed as human foods” (§ 211.1(c)).

This means that an OTC item with a borderline drug claim could sometimes avoid certain Part 211 stipulations – though only under specific conditions spelled out in the Federal Register.

Why This Matters in Practice

If you produce a nasal spray that’s also classified as a biologic (for example, containing live or attenuated organisms), you’ll need to comply with both Part 211 and the relevant biologics rules in parts 600–680.

If you manufacture an OTC chewable supplement that can be considered food, you might qualify for partial exemptions, although, in practice, FDA seldom grants broad exceptions lightly. Always confirm with a legal or regulatory expert.

Who Must Comply?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers producing finished products for human use.

Contract manufacturing or packaging facilities that handle drug products for other companies.

Quality control units responsible for testing and releasing finished pharmaceuticals.

6 Common Mistakes and Practical Solutions

Rather than listing out every paragraph of the regulation, let’s focus on how its rules intersect with real challenges manufacturers face.

1) Underestimating the Role of the Quality Control Unit (QCU)

In some facilities, the Quality Control Unit is treated as a rubber-stamp department, lacking resources or authority to reject defective components or finished products.

This is a red flag because 21 CFR Part 211 places final authority for approving or rejecting all components and final drug products on the QCU’s shoulders.

If the QCU is weak, so is your compliance posture.

Regulatory Basis

Quality Control Responsibilities: The regulation states the QCU “shall have the responsibility and authority to approve or reject all components, drug product containers, closures, in-process materials, packaging materials, labeling, and drug products” (ref. § 211.22).

Investigations and Approval: It must also review production records, investigate errors, and manage disposition of returned or salvaged products.

Practical Example

Let’s say a small tablet manufacturer receives a questionable batch of excipients.

Production wants to keep lines running and tries to bypass QCU approval.

If the QCU can’t veto that decision – due to a lack of budget, staff, or managerial support – it might let subpar materials into the manufacturing stream.

This sets the stage for product failures, consumer complaints, or recalls.

Solutions

Grant Real Authority: Include a formal statement in your Quality Manual clarifying QCU’s power to halt production or reject shipments with top management backing.

Ensure Adequate Lab Facilities: Provide the QCU with enough space, instruments, and skilled analysts to handle incoming inspections, in-process testing, and batch-release decisions.

Link Investigations to Production: If a batch is suspect, the QCU should expand that investigation to see if other batches might be impacted, ensuring no hidden quality issues.

Why It Works

When the QCU has unambiguous oversight, mistakes or subpar materials can be caught early and before they become expensive, brand-damaging catastrophes.

2) Incomplete Documentation and Data Integrity Lapses

Missing batch records, inaccurate cleaning logs, backdated analytical data, or “unofficial” test runs are all red flags in FDA inspections.

21 CFR Part 211 demands comprehensive records at each stage of drug manufacturing and explicitly warns against undocumented data manipulations.

Regulatory Basis

Laboratory Records: You must keep “complete data derived from all tests necessary to assure compliance,” including raw data, method details, calculations, and signatures of those who performed and reviewed them (ref. § 211.194).

Production Record Review: The regulation also insists that QC reviews “all drug product production and control records” before releasing a batch (ref. § 211.192).

Practical Example

A contract lab attempts multiple “trial” injections until they get a passing result, discarding any earlier “bad” data.

If an FDA inspector checks instrument logs and sees unaccounted injection sequences, that’s a huge data integrity breach.

Another scenario: A production line logs finished product weight checks at the end of a shift, hours after they were supposed to happen, with no real-time documentation.

Solutions

Adopt Electronic Systems with Audit Trails: Use validated software that logs each data entry, preventing unauthorized changes or deletions.

Train Staff on ALCOA+ Principles: (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available). Make employees understand that every piece of data must be documented as it happens.

Frequent Internal Audits: Check random sets of production and lab records to confirm real-time documentation. If you find a suspicious log entry, investigate.

Why It Works

Complete and transparent records give regulators confidence in your product.

Data integrity meets the letter of 21 CFR Part 211 and helps you maintain consistent quality over time.

3) Lax Control Over Components and Containers

Some manufacturers rely entirely on supplier Certificates of Analysis (COAs) without verifying identity or purity themselves.

Others fail to quarantine incoming materials or co-mingle them with approved stock.

Over time, such practices can invite contaminated or mislabeled items into production.

Regulatory Basis

Receipt, Storage, and Testing of Components: The regulation requires quarantining each container of components until tested and approved. For each lot, you must perform at least one specific identity test (ref. § 211.84(d)(1)).

Handling Rejected Materials: If something fails your specs, label it as “Rejected” and isolate it so it’s not accidentally used.

Practical Example

A soft-gel capsule firm begins using a new gelatin source, trusting the supplier’s COA, stating “meets USP standard.”

Later, they discover the gelatin’s bloom strength is off, causing capsules to leak.

If they had done an identity or bloom-strength test themselves, they’d have caught the issue long before producing thousands of defective capsules.

Solutions

At Least One Identity Test: Even if you generally trust a supplier, the regulation mandates confirming each lot’s identity in-house.

Status Labeling: Use color-coded or barcode-coded tags indicating “Quarantined,” “Approved,” or “Rejected.” Keep them physically separated to avoid mix-ups.

Periodic Supplier Validation: Audit your critical raw material vendors. Ask for process flowcharts, testing procedures, and a track record of consistent COA results.

Why It Works

Systematically testing and tagging components ensures that only verified, high-quality materials enter your production lines. This upfront diligence prevents bigger headaches downstream, like failed batches or consumer complaints.

4) Poorly Enforced In-Process Checks

CGMP emphasizes in-process testing to ensure that each stage of production is proceeding correctly.

However, some companies skip or rush these checks, hoping final release testing alone will catch any issues.

That’s a dangerous gamble because end-stage testing won’t always reveal process-related problems.

Regulatory Basis

Written Procedures for Production and Process Control: The regulation says each batch must “have the identity, strength, quality, and purity they purport” to possess. You’re expected to follow pre-approved instructions at each manufacturing step, including specific sampling or testing intervals.

In-Process Materials: Whether it’s measuring weight variation for tablets or checking bioburden in non-sterile liquids, you need “appropriate control procedures” designed to prevent variability (ref. parts of § 211.110).

Practical Example

A topical cream manufacturer has an SOP specifying every 1,000 jars, and an operator checks viscosity to confirm uniform mixing.

Under production pressure, operators only test once at the start and once at the end.

If a mixing blade malfunctions midway, jars produced during that gap might differ in consistency or efficacy – yet no one notices until consumers complain.

Solutions

Embed In-Process Testing in SOPs: Spell out sampling frequency (“every X minutes or Y units”), acceptance criteria, and operators' actions if results are off.

Immediate Documentation: Record each in-process result in real time. If you wait hours, data can be “filled in” from memory or guesswork, raising compliance concerns.

Link Changes to Revalidation: If you alter mixing speeds, blend times, or temperature parameters, confirm you can still meet in-process specs.

Why It Works

Consistent in-process checks let you spot and correct deviations early, reducing product loss and guaranteeing uniform batches.

This also satisfies the regulation’s requirement to monitor critical phases, preventing substandard goods from reaching consumers.

5) Neglecting Facility and Equipment Standards

21 CFR Part 211 expects you to maintain suitable buildings and equipment to avoid cross-contamination, ensure proper sanitation, and maintain robust ventilation.

If your facility is cramped, poorly lit, or equipment cleaning schedules are seldom updated, you risk major compliance violations.

Regulatory Basis

Buildings and Facilities: The regulation highlights the need for adequate space to “prevent mixups” and “facilitate cleaning, maintenance, and proper operations.” Aseptic processing demands smooth, easily cleanable surfaces, filtered air, and environmental monitoring.

Equipment Construction and Maintenance: Surfaces in contact with drug products must not be reactive or shed contaminants. Written cleaning procedures are mandatory, along with logs showing who cleaned what and when.

Practical Example

A penicillin manufacturer attempts to produce a non-penicillin antibiotic in the same building – without fully separated air systems or dust controls.

Later, trace penicillin contamination is found in the antibiotic, prompting a swift FDA citation because mixing penicillin with other drug lines is specifically regulated.

Solutions

Dedicated Areas: Separate or define areas for quarantined goods, packaging materials, rejects, and different product families. This is crucial if penicillin is involved.

Written Sanitation and Maintenance Schedules: Outline how often floors, walls, and equipment are cleaned, which agents you use, and how you record completion.

Environmental Monitoring: If you produce sterile or high-sensitivity drugs, run routine air particle counts and microbial swabs to confirm compliance.

Why It Works

Proper building layout and equipment upkeep help you avoid cross-contamination or adulteration, thus meeting the fundamental CGMP principle of consistent, contaminant-free production.

6) Mishandling Returned, Rejected, or Salvaged Products

When returned drug products come back from the field (maybe due to shipping errors or consumer complaints), some manufacturers hastily re-label or re-blend them with fresh stock. Others salvage goods that were exposed to harsh conditions (e.g., floods, fires) without thorough testing.

Regulatory Basis

Returned Drug Products: The regulation states that if there’s any doubt about how a product was stored or shipped, that item “shall be destroyed” unless tests prove it’s still safe and intact.

Salvaging After Accidents: If products face extremes (temperature, humidity, smoke, etc.), you can salvage them only after “evidence from laboratory tests and assays” confirms they meet all standards of identity, strength, quality, and purity.

Practical Example

A distribution error sends a pallet of syrups to a remote warehouse for months without temperature control.

They come back to the manufacturing site with possible microbial contamination.

If you simply re-box them for sale, ignoring thorough retesting, you’re risking consumer health and an immediate FDA violation.

Solutions

Hold and Investigate: Quarantine every returned lot. Document the reason for return, location, or shipping conditions, and do lab checks as needed.

Adequate Tests for Reprocessing: If you must reprocess, outline each step in writing: what new controls ensure it meets original specs?

Destroy or Document: If safety or purity are in doubt, the regulation strongly suggests destroying the product to avoid risk.

Why It Works

Clear SOPs for handling returns or salvaging ensure questionable products don’t re-enter commerce. This protects patients and meets the regulation’s standard that all batches must conform to labeled specifications.

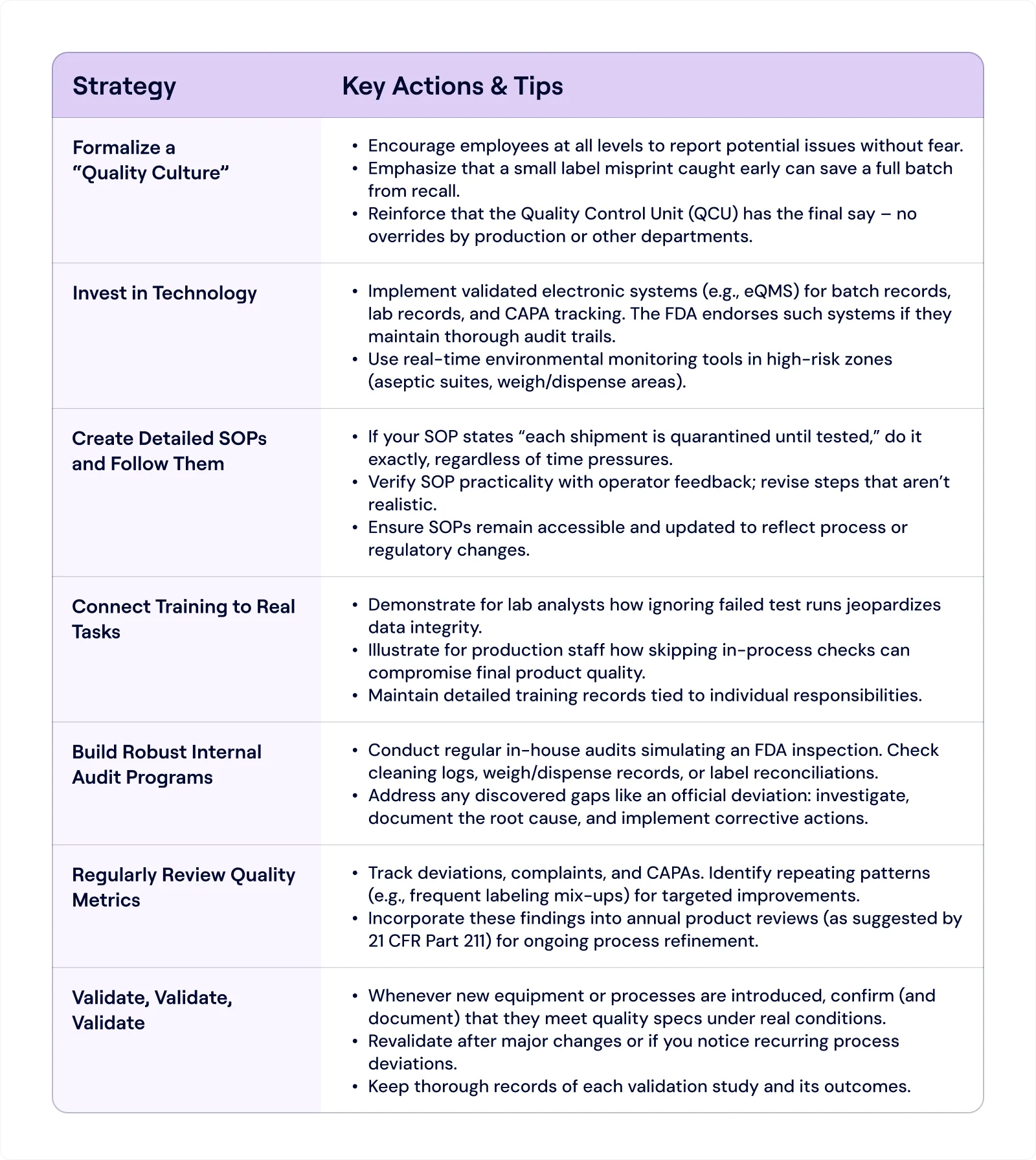

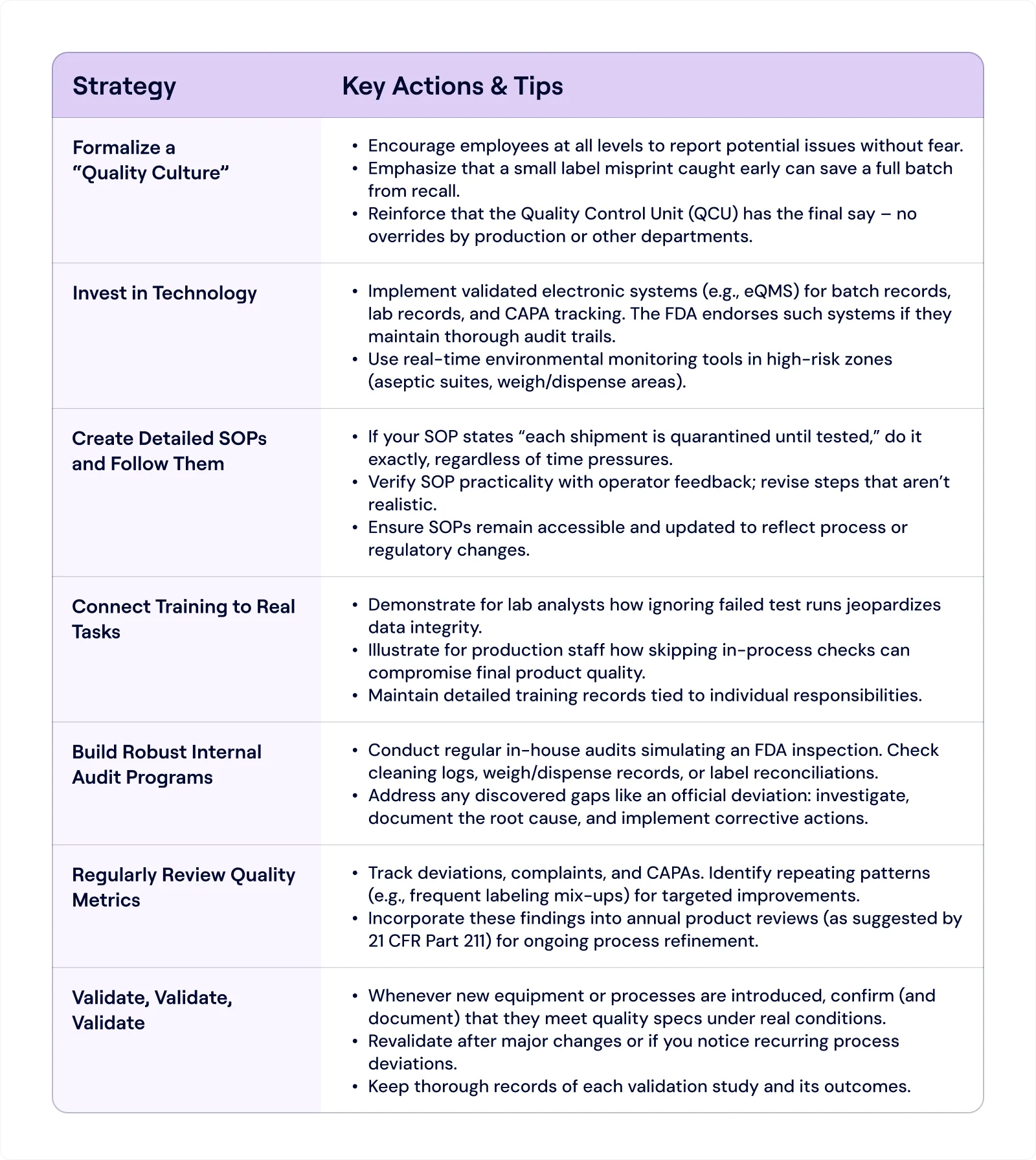

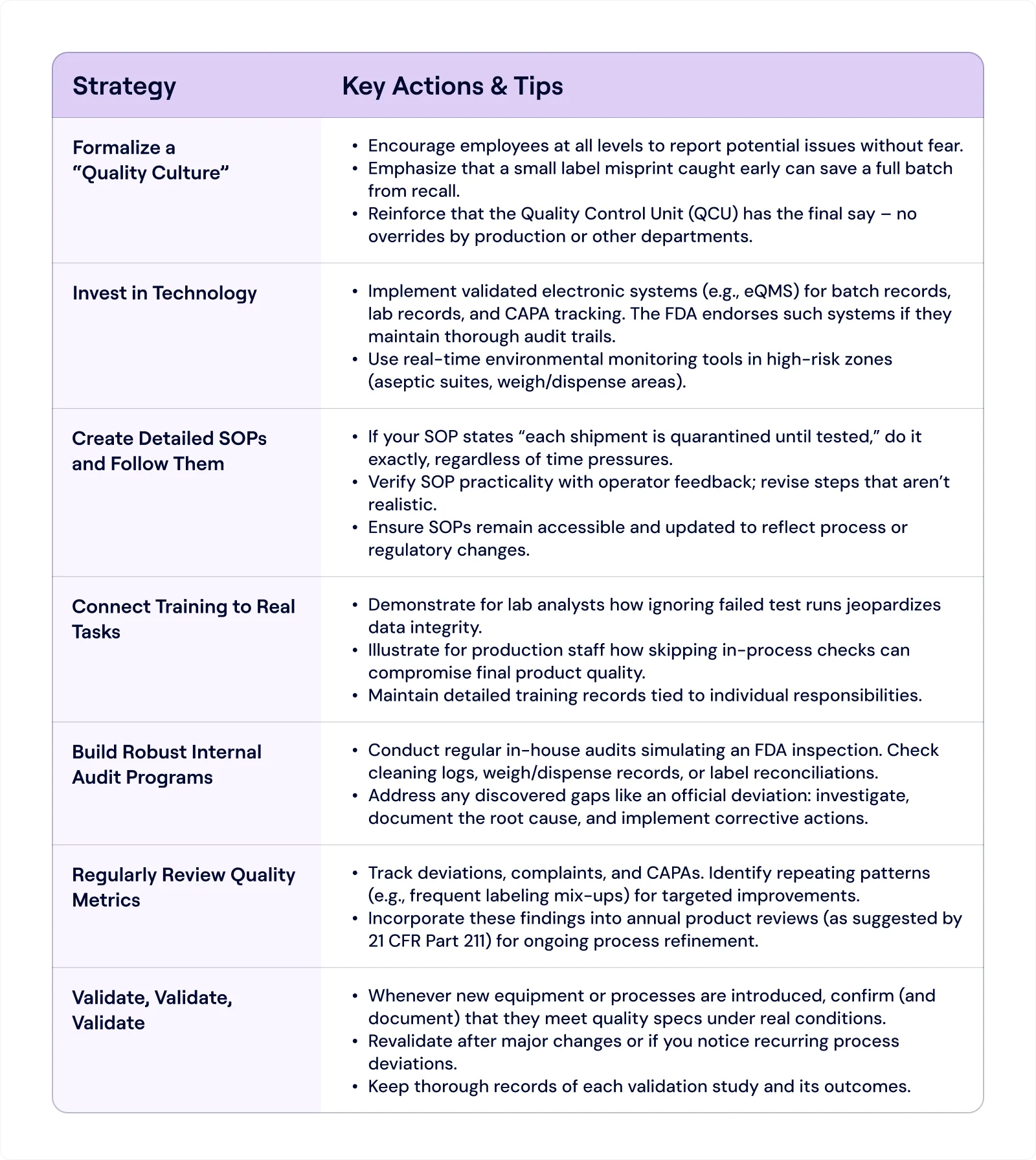

Further Strategies for Smooth Compliance With FDA 21 CFR Part 211

Given these pitfalls, how can you fortify your operations against them? Below are some strategies to consider:

Practical Example: Putting It All Together

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario:

Company A makes oral solid dosage forms (tablets) using outsourced excipients. They have a QCU on paper, but that unit rarely rejects materials.

Their production line seldom performs in-process tablet weight checks, and they rely fully on the final “blend uniformity test.”

They also store “approved” and “unapproved” excipient drums in the same area due to space constraints.

What Goes Wrong?

A supplier’s excipient lot has variable particle size not caught by any in-house identity test.

During mixing, uniformity is off, but because in-process checks are skipped, nobody notices.

Final tablets fail dissolution tests, but by then, thousands are produced.

Attempting to salvage some tablets, the firm runs partial re-blending with a fresh excipient, contrary to the original SOP.

Result:

FDA inspection uncovers incomplete documentation for re-blending, no real-time batch data, a powerless QCU, and co-mingled raw materials.

The facility receives a warning letter citing specific references to 21 CFR Part 211 (lack of identity testing on each component lot, missing or inaccurate production records, unvalidated rework procedure, and insufficient QC oversight).

Rescue Plan:

Company A invests in an eQMS (electronic Quality Management System) that enforces quarantine status for each excipient lot. Operators must scan barcodes before usage, preventing accidental use of unapproved lots.

They revamp in-process checks with a standard schedule (e.g., weigh 20 tablets every 30 minutes). Results are recorded immediately on digital forms, each time referencing the specific batch.

The QCU receives additional staffing and a dedicated lab area for routine identity tests on incoming excipients, as the regulation demands.

All re-blending or reprocessing steps go through a documented approval process to show compliance with 21 CFR Part 211 standards.

By aligning each fix with the letter and spirit of 21 CFR Part 211, Company A gets back on track, steadily restoring trust among regulators and customers.

Elevate Your FDA 21 CFR Part 211 Compliance With Signify

As seen in Company A’s journey, transforming a reactive and disjointed system into a proactive, well-documented, and transparent process can rapidly turn non-compliance around.

Investing in real-time monitoring, quality checks, and an empowered Quality Control Unit meets the minimums of 21 CFR Part 211 and fosters a culture of excellence for regulators and customers to appreciate.

Signify offers a modern, comprehensive platform that simplifies this transformation:

Continuous Compliance: Leverage AI-generated smart checklists to spot issues in SOPs, packaging labels, or raw material documentation before they escalate.

Automated Evidence Traceability: Instantly locate and reference critical sections in your quality records, enhancing transparency and speeding up audits.

Real-Time Risk Monitoring: Conduct on-the-fly conformity assessments, automatically detect changes in regulations, and stay informed of internal document updates that might introduce nonconformities.

By integrating Signify into your operations, you gain the agility to adapt to evolving regulations, pinpoint and address compliance gaps, and demonstrate unwavering adherence to 21 CFR Part 211.

Ready to modernize your compliance strategy?

Schedule a demo and explore how Signify can streamline your regulatory and quality workflows.

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most highly regulated sectors worldwide, and for good reason: any lapse in quality can directly impact patient health.

In the United States, 21 CFR Part 211 sits at the core of the FDA’s current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) requirements for finished pharmaceuticals.

These regulations can seem a bit much, but they exist to protect consumers by ensuring products are consistently safe, pure, and potent.

The Historical Underpinning: Why Part 211 Exists

Modern pharmaceutical regulations have roots dating back to early 20th-century reforms when unsafe or fraudulent medicines prompted lawmakers to demand higher standards of manufacturing and distribution.

Over time, repeated incidents – from tainted cough syrups to eye drops contamination – refined the scope of these rules.

In the late 70s, the FDA finalized 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211, which are core CGMP regulations. Together, they outline the responsibilities of drug manufacturers to ensure drug purity, potency, and consistency.

Part 210 provides overarching definitions and general provisions.

Part 211 builds on that foundation by specifying requirements for everything from personnel qualifications to detailed recordkeeping.

Purpose of 21 CFR Part 211

Under 21 CFR § 211.1, the FDA clarifies that Part 211 contains the “minimum current good manufacturing practice” (CGMP) for preparing drug products (excluding positron emission tomography (PET) drugs) for both humans and animals.

The phrase “minimum” is important: many companies opt for even stricter standards based on their risk assessments.

The main goal of 21 CFR Part 211 is to guarantee that every drug product meets its intended specifications and is safe for consumers.

By establishing detailed guidelines for facilities, equipment, processes, training, and documentation, Part 211 helps manufacturers:

Prevent errors and inconsistencies.

Maintain product quality and safety from the earliest production stages to final distribution.

Protect patients from ineffective or contaminated medications.

Unlike less-regulated sectors, drug manufacturing requires rigorous oversight of everything (from container closures to personnel qualifications) because patient safety is on the line.

While cosmetics regulations, such as Part 701 for labeling, have their own standards, Part 211 has more stringent requirements because pharmaceutical products pose a higher risk to consumer safety.

Additional considerations:

Part 211 interacts with other FDA regulations.

For drugs that are also biologics (e.g., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies), or human cells and tissues regulated under parts 600 through 680 and part 1271, those specialized rules “supplement and do not supersede” Part 211.

In other words, if there’s a conflict, the more specific or stricter requirement prevails (§ 211.1(b)).

Potential exemptions for certain OTC products that are also foods might apply under part 110, 117, or 113–129 if the product is “ordinarily marketed and consumed as human foods” (§ 211.1(c)).

This means that an OTC item with a borderline drug claim could sometimes avoid certain Part 211 stipulations – though only under specific conditions spelled out in the Federal Register.

Why This Matters in Practice

If you produce a nasal spray that’s also classified as a biologic (for example, containing live or attenuated organisms), you’ll need to comply with both Part 211 and the relevant biologics rules in parts 600–680.

If you manufacture an OTC chewable supplement that can be considered food, you might qualify for partial exemptions, although, in practice, FDA seldom grants broad exceptions lightly. Always confirm with a legal or regulatory expert.

Who Must Comply?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers producing finished products for human use.

Contract manufacturing or packaging facilities that handle drug products for other companies.

Quality control units responsible for testing and releasing finished pharmaceuticals.

6 Common Mistakes and Practical Solutions

Rather than listing out every paragraph of the regulation, let’s focus on how its rules intersect with real challenges manufacturers face.

1) Underestimating the Role of the Quality Control Unit (QCU)

In some facilities, the Quality Control Unit is treated as a rubber-stamp department, lacking resources or authority to reject defective components or finished products.

This is a red flag because 21 CFR Part 211 places final authority for approving or rejecting all components and final drug products on the QCU’s shoulders.

If the QCU is weak, so is your compliance posture.

Regulatory Basis

Quality Control Responsibilities: The regulation states the QCU “shall have the responsibility and authority to approve or reject all components, drug product containers, closures, in-process materials, packaging materials, labeling, and drug products” (ref. § 211.22).

Investigations and Approval: It must also review production records, investigate errors, and manage disposition of returned or salvaged products.

Practical Example

Let’s say a small tablet manufacturer receives a questionable batch of excipients.

Production wants to keep lines running and tries to bypass QCU approval.

If the QCU can’t veto that decision – due to a lack of budget, staff, or managerial support – it might let subpar materials into the manufacturing stream.

This sets the stage for product failures, consumer complaints, or recalls.

Solutions

Grant Real Authority: Include a formal statement in your Quality Manual clarifying QCU’s power to halt production or reject shipments with top management backing.

Ensure Adequate Lab Facilities: Provide the QCU with enough space, instruments, and skilled analysts to handle incoming inspections, in-process testing, and batch-release decisions.

Link Investigations to Production: If a batch is suspect, the QCU should expand that investigation to see if other batches might be impacted, ensuring no hidden quality issues.

Why It Works

When the QCU has unambiguous oversight, mistakes or subpar materials can be caught early and before they become expensive, brand-damaging catastrophes.

2) Incomplete Documentation and Data Integrity Lapses

Missing batch records, inaccurate cleaning logs, backdated analytical data, or “unofficial” test runs are all red flags in FDA inspections.

21 CFR Part 211 demands comprehensive records at each stage of drug manufacturing and explicitly warns against undocumented data manipulations.

Regulatory Basis

Laboratory Records: You must keep “complete data derived from all tests necessary to assure compliance,” including raw data, method details, calculations, and signatures of those who performed and reviewed them (ref. § 211.194).

Production Record Review: The regulation also insists that QC reviews “all drug product production and control records” before releasing a batch (ref. § 211.192).

Practical Example

A contract lab attempts multiple “trial” injections until they get a passing result, discarding any earlier “bad” data.

If an FDA inspector checks instrument logs and sees unaccounted injection sequences, that’s a huge data integrity breach.

Another scenario: A production line logs finished product weight checks at the end of a shift, hours after they were supposed to happen, with no real-time documentation.

Solutions

Adopt Electronic Systems with Audit Trails: Use validated software that logs each data entry, preventing unauthorized changes or deletions.

Train Staff on ALCOA+ Principles: (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available). Make employees understand that every piece of data must be documented as it happens.

Frequent Internal Audits: Check random sets of production and lab records to confirm real-time documentation. If you find a suspicious log entry, investigate.

Why It Works

Complete and transparent records give regulators confidence in your product.

Data integrity meets the letter of 21 CFR Part 211 and helps you maintain consistent quality over time.

3) Lax Control Over Components and Containers

Some manufacturers rely entirely on supplier Certificates of Analysis (COAs) without verifying identity or purity themselves.

Others fail to quarantine incoming materials or co-mingle them with approved stock.

Over time, such practices can invite contaminated or mislabeled items into production.

Regulatory Basis

Receipt, Storage, and Testing of Components: The regulation requires quarantining each container of components until tested and approved. For each lot, you must perform at least one specific identity test (ref. § 211.84(d)(1)).

Handling Rejected Materials: If something fails your specs, label it as “Rejected” and isolate it so it’s not accidentally used.

Practical Example

A soft-gel capsule firm begins using a new gelatin source, trusting the supplier’s COA, stating “meets USP standard.”

Later, they discover the gelatin’s bloom strength is off, causing capsules to leak.

If they had done an identity or bloom-strength test themselves, they’d have caught the issue long before producing thousands of defective capsules.

Solutions

At Least One Identity Test: Even if you generally trust a supplier, the regulation mandates confirming each lot’s identity in-house.

Status Labeling: Use color-coded or barcode-coded tags indicating “Quarantined,” “Approved,” or “Rejected.” Keep them physically separated to avoid mix-ups.

Periodic Supplier Validation: Audit your critical raw material vendors. Ask for process flowcharts, testing procedures, and a track record of consistent COA results.

Why It Works

Systematically testing and tagging components ensures that only verified, high-quality materials enter your production lines. This upfront diligence prevents bigger headaches downstream, like failed batches or consumer complaints.

4) Poorly Enforced In-Process Checks

CGMP emphasizes in-process testing to ensure that each stage of production is proceeding correctly.

However, some companies skip or rush these checks, hoping final release testing alone will catch any issues.

That’s a dangerous gamble because end-stage testing won’t always reveal process-related problems.

Regulatory Basis

Written Procedures for Production and Process Control: The regulation says each batch must “have the identity, strength, quality, and purity they purport” to possess. You’re expected to follow pre-approved instructions at each manufacturing step, including specific sampling or testing intervals.

In-Process Materials: Whether it’s measuring weight variation for tablets or checking bioburden in non-sterile liquids, you need “appropriate control procedures” designed to prevent variability (ref. parts of § 211.110).

Practical Example

A topical cream manufacturer has an SOP specifying every 1,000 jars, and an operator checks viscosity to confirm uniform mixing.

Under production pressure, operators only test once at the start and once at the end.

If a mixing blade malfunctions midway, jars produced during that gap might differ in consistency or efficacy – yet no one notices until consumers complain.

Solutions

Embed In-Process Testing in SOPs: Spell out sampling frequency (“every X minutes or Y units”), acceptance criteria, and operators' actions if results are off.

Immediate Documentation: Record each in-process result in real time. If you wait hours, data can be “filled in” from memory or guesswork, raising compliance concerns.

Link Changes to Revalidation: If you alter mixing speeds, blend times, or temperature parameters, confirm you can still meet in-process specs.

Why It Works

Consistent in-process checks let you spot and correct deviations early, reducing product loss and guaranteeing uniform batches.

This also satisfies the regulation’s requirement to monitor critical phases, preventing substandard goods from reaching consumers.

5) Neglecting Facility and Equipment Standards

21 CFR Part 211 expects you to maintain suitable buildings and equipment to avoid cross-contamination, ensure proper sanitation, and maintain robust ventilation.

If your facility is cramped, poorly lit, or equipment cleaning schedules are seldom updated, you risk major compliance violations.

Regulatory Basis

Buildings and Facilities: The regulation highlights the need for adequate space to “prevent mixups” and “facilitate cleaning, maintenance, and proper operations.” Aseptic processing demands smooth, easily cleanable surfaces, filtered air, and environmental monitoring.

Equipment Construction and Maintenance: Surfaces in contact with drug products must not be reactive or shed contaminants. Written cleaning procedures are mandatory, along with logs showing who cleaned what and when.

Practical Example

A penicillin manufacturer attempts to produce a non-penicillin antibiotic in the same building – without fully separated air systems or dust controls.

Later, trace penicillin contamination is found in the antibiotic, prompting a swift FDA citation because mixing penicillin with other drug lines is specifically regulated.

Solutions

Dedicated Areas: Separate or define areas for quarantined goods, packaging materials, rejects, and different product families. This is crucial if penicillin is involved.

Written Sanitation and Maintenance Schedules: Outline how often floors, walls, and equipment are cleaned, which agents you use, and how you record completion.

Environmental Monitoring: If you produce sterile or high-sensitivity drugs, run routine air particle counts and microbial swabs to confirm compliance.

Why It Works

Proper building layout and equipment upkeep help you avoid cross-contamination or adulteration, thus meeting the fundamental CGMP principle of consistent, contaminant-free production.

6) Mishandling Returned, Rejected, or Salvaged Products

When returned drug products come back from the field (maybe due to shipping errors or consumer complaints), some manufacturers hastily re-label or re-blend them with fresh stock. Others salvage goods that were exposed to harsh conditions (e.g., floods, fires) without thorough testing.

Regulatory Basis

Returned Drug Products: The regulation states that if there’s any doubt about how a product was stored or shipped, that item “shall be destroyed” unless tests prove it’s still safe and intact.

Salvaging After Accidents: If products face extremes (temperature, humidity, smoke, etc.), you can salvage them only after “evidence from laboratory tests and assays” confirms they meet all standards of identity, strength, quality, and purity.

Practical Example

A distribution error sends a pallet of syrups to a remote warehouse for months without temperature control.

They come back to the manufacturing site with possible microbial contamination.

If you simply re-box them for sale, ignoring thorough retesting, you’re risking consumer health and an immediate FDA violation.

Solutions

Hold and Investigate: Quarantine every returned lot. Document the reason for return, location, or shipping conditions, and do lab checks as needed.

Adequate Tests for Reprocessing: If you must reprocess, outline each step in writing: what new controls ensure it meets original specs?

Destroy or Document: If safety or purity are in doubt, the regulation strongly suggests destroying the product to avoid risk.

Why It Works

Clear SOPs for handling returns or salvaging ensure questionable products don’t re-enter commerce. This protects patients and meets the regulation’s standard that all batches must conform to labeled specifications.

Further Strategies for Smooth Compliance With FDA 21 CFR Part 211

Given these pitfalls, how can you fortify your operations against them? Below are some strategies to consider:

Practical Example: Putting It All Together

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario:

Company A makes oral solid dosage forms (tablets) using outsourced excipients. They have a QCU on paper, but that unit rarely rejects materials.

Their production line seldom performs in-process tablet weight checks, and they rely fully on the final “blend uniformity test.”

They also store “approved” and “unapproved” excipient drums in the same area due to space constraints.

What Goes Wrong?

A supplier’s excipient lot has variable particle size not caught by any in-house identity test.

During mixing, uniformity is off, but because in-process checks are skipped, nobody notices.

Final tablets fail dissolution tests, but by then, thousands are produced.

Attempting to salvage some tablets, the firm runs partial re-blending with a fresh excipient, contrary to the original SOP.

Result:

FDA inspection uncovers incomplete documentation for re-blending, no real-time batch data, a powerless QCU, and co-mingled raw materials.

The facility receives a warning letter citing specific references to 21 CFR Part 211 (lack of identity testing on each component lot, missing or inaccurate production records, unvalidated rework procedure, and insufficient QC oversight).

Rescue Plan:

Company A invests in an eQMS (electronic Quality Management System) that enforces quarantine status for each excipient lot. Operators must scan barcodes before usage, preventing accidental use of unapproved lots.

They revamp in-process checks with a standard schedule (e.g., weigh 20 tablets every 30 minutes). Results are recorded immediately on digital forms, each time referencing the specific batch.

The QCU receives additional staffing and a dedicated lab area for routine identity tests on incoming excipients, as the regulation demands.

All re-blending or reprocessing steps go through a documented approval process to show compliance with 21 CFR Part 211 standards.

By aligning each fix with the letter and spirit of 21 CFR Part 211, Company A gets back on track, steadily restoring trust among regulators and customers.

Elevate Your FDA 21 CFR Part 211 Compliance With Signify

As seen in Company A’s journey, transforming a reactive and disjointed system into a proactive, well-documented, and transparent process can rapidly turn non-compliance around.

Investing in real-time monitoring, quality checks, and an empowered Quality Control Unit meets the minimums of 21 CFR Part 211 and fosters a culture of excellence for regulators and customers to appreciate.

Signify offers a modern, comprehensive platform that simplifies this transformation:

Continuous Compliance: Leverage AI-generated smart checklists to spot issues in SOPs, packaging labels, or raw material documentation before they escalate.

Automated Evidence Traceability: Instantly locate and reference critical sections in your quality records, enhancing transparency and speeding up audits.

Real-Time Risk Monitoring: Conduct on-the-fly conformity assessments, automatically detect changes in regulations, and stay informed of internal document updates that might introduce nonconformities.

By integrating Signify into your operations, you gain the agility to adapt to evolving regulations, pinpoint and address compliance gaps, and demonstrate unwavering adherence to 21 CFR Part 211.

Ready to modernize your compliance strategy?

Schedule a demo and explore how Signify can streamline your regulatory and quality workflows.

The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most highly regulated sectors worldwide, and for good reason: any lapse in quality can directly impact patient health.

In the United States, 21 CFR Part 211 sits at the core of the FDA’s current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) requirements for finished pharmaceuticals.

These regulations can seem a bit much, but they exist to protect consumers by ensuring products are consistently safe, pure, and potent.

The Historical Underpinning: Why Part 211 Exists

Modern pharmaceutical regulations have roots dating back to early 20th-century reforms when unsafe or fraudulent medicines prompted lawmakers to demand higher standards of manufacturing and distribution.

Over time, repeated incidents – from tainted cough syrups to eye drops contamination – refined the scope of these rules.

In the late 70s, the FDA finalized 21 CFR Parts 210 and 211, which are core CGMP regulations. Together, they outline the responsibilities of drug manufacturers to ensure drug purity, potency, and consistency.

Part 210 provides overarching definitions and general provisions.

Part 211 builds on that foundation by specifying requirements for everything from personnel qualifications to detailed recordkeeping.

Purpose of 21 CFR Part 211

Under 21 CFR § 211.1, the FDA clarifies that Part 211 contains the “minimum current good manufacturing practice” (CGMP) for preparing drug products (excluding positron emission tomography (PET) drugs) for both humans and animals.

The phrase “minimum” is important: many companies opt for even stricter standards based on their risk assessments.

The main goal of 21 CFR Part 211 is to guarantee that every drug product meets its intended specifications and is safe for consumers.

By establishing detailed guidelines for facilities, equipment, processes, training, and documentation, Part 211 helps manufacturers:

Prevent errors and inconsistencies.

Maintain product quality and safety from the earliest production stages to final distribution.

Protect patients from ineffective or contaminated medications.

Unlike less-regulated sectors, drug manufacturing requires rigorous oversight of everything (from container closures to personnel qualifications) because patient safety is on the line.

While cosmetics regulations, such as Part 701 for labeling, have their own standards, Part 211 has more stringent requirements because pharmaceutical products pose a higher risk to consumer safety.

Additional considerations:

Part 211 interacts with other FDA regulations.

For drugs that are also biologics (e.g., vaccines, monoclonal antibodies), or human cells and tissues regulated under parts 600 through 680 and part 1271, those specialized rules “supplement and do not supersede” Part 211.

In other words, if there’s a conflict, the more specific or stricter requirement prevails (§ 211.1(b)).

Potential exemptions for certain OTC products that are also foods might apply under part 110, 117, or 113–129 if the product is “ordinarily marketed and consumed as human foods” (§ 211.1(c)).

This means that an OTC item with a borderline drug claim could sometimes avoid certain Part 211 stipulations – though only under specific conditions spelled out in the Federal Register.

Why This Matters in Practice

If you produce a nasal spray that’s also classified as a biologic (for example, containing live or attenuated organisms), you’ll need to comply with both Part 211 and the relevant biologics rules in parts 600–680.

If you manufacture an OTC chewable supplement that can be considered food, you might qualify for partial exemptions, although, in practice, FDA seldom grants broad exceptions lightly. Always confirm with a legal or regulatory expert.

Who Must Comply?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers producing finished products for human use.

Contract manufacturing or packaging facilities that handle drug products for other companies.

Quality control units responsible for testing and releasing finished pharmaceuticals.

6 Common Mistakes and Practical Solutions

Rather than listing out every paragraph of the regulation, let’s focus on how its rules intersect with real challenges manufacturers face.

1) Underestimating the Role of the Quality Control Unit (QCU)

In some facilities, the Quality Control Unit is treated as a rubber-stamp department, lacking resources or authority to reject defective components or finished products.

This is a red flag because 21 CFR Part 211 places final authority for approving or rejecting all components and final drug products on the QCU’s shoulders.

If the QCU is weak, so is your compliance posture.

Regulatory Basis

Quality Control Responsibilities: The regulation states the QCU “shall have the responsibility and authority to approve or reject all components, drug product containers, closures, in-process materials, packaging materials, labeling, and drug products” (ref. § 211.22).

Investigations and Approval: It must also review production records, investigate errors, and manage disposition of returned or salvaged products.

Practical Example

Let’s say a small tablet manufacturer receives a questionable batch of excipients.

Production wants to keep lines running and tries to bypass QCU approval.

If the QCU can’t veto that decision – due to a lack of budget, staff, or managerial support – it might let subpar materials into the manufacturing stream.

This sets the stage for product failures, consumer complaints, or recalls.

Solutions

Grant Real Authority: Include a formal statement in your Quality Manual clarifying QCU’s power to halt production or reject shipments with top management backing.

Ensure Adequate Lab Facilities: Provide the QCU with enough space, instruments, and skilled analysts to handle incoming inspections, in-process testing, and batch-release decisions.

Link Investigations to Production: If a batch is suspect, the QCU should expand that investigation to see if other batches might be impacted, ensuring no hidden quality issues.

Why It Works

When the QCU has unambiguous oversight, mistakes or subpar materials can be caught early and before they become expensive, brand-damaging catastrophes.

2) Incomplete Documentation and Data Integrity Lapses

Missing batch records, inaccurate cleaning logs, backdated analytical data, or “unofficial” test runs are all red flags in FDA inspections.

21 CFR Part 211 demands comprehensive records at each stage of drug manufacturing and explicitly warns against undocumented data manipulations.

Regulatory Basis

Laboratory Records: You must keep “complete data derived from all tests necessary to assure compliance,” including raw data, method details, calculations, and signatures of those who performed and reviewed them (ref. § 211.194).

Production Record Review: The regulation also insists that QC reviews “all drug product production and control records” before releasing a batch (ref. § 211.192).

Practical Example

A contract lab attempts multiple “trial” injections until they get a passing result, discarding any earlier “bad” data.

If an FDA inspector checks instrument logs and sees unaccounted injection sequences, that’s a huge data integrity breach.

Another scenario: A production line logs finished product weight checks at the end of a shift, hours after they were supposed to happen, with no real-time documentation.

Solutions

Adopt Electronic Systems with Audit Trails: Use validated software that logs each data entry, preventing unauthorized changes or deletions.

Train Staff on ALCOA+ Principles: (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, plus Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available). Make employees understand that every piece of data must be documented as it happens.

Frequent Internal Audits: Check random sets of production and lab records to confirm real-time documentation. If you find a suspicious log entry, investigate.

Why It Works

Complete and transparent records give regulators confidence in your product.

Data integrity meets the letter of 21 CFR Part 211 and helps you maintain consistent quality over time.

3) Lax Control Over Components and Containers

Some manufacturers rely entirely on supplier Certificates of Analysis (COAs) without verifying identity or purity themselves.

Others fail to quarantine incoming materials or co-mingle them with approved stock.

Over time, such practices can invite contaminated or mislabeled items into production.

Regulatory Basis

Receipt, Storage, and Testing of Components: The regulation requires quarantining each container of components until tested and approved. For each lot, you must perform at least one specific identity test (ref. § 211.84(d)(1)).

Handling Rejected Materials: If something fails your specs, label it as “Rejected” and isolate it so it’s not accidentally used.

Practical Example

A soft-gel capsule firm begins using a new gelatin source, trusting the supplier’s COA, stating “meets USP standard.”

Later, they discover the gelatin’s bloom strength is off, causing capsules to leak.

If they had done an identity or bloom-strength test themselves, they’d have caught the issue long before producing thousands of defective capsules.

Solutions

At Least One Identity Test: Even if you generally trust a supplier, the regulation mandates confirming each lot’s identity in-house.

Status Labeling: Use color-coded or barcode-coded tags indicating “Quarantined,” “Approved,” or “Rejected.” Keep them physically separated to avoid mix-ups.

Periodic Supplier Validation: Audit your critical raw material vendors. Ask for process flowcharts, testing procedures, and a track record of consistent COA results.

Why It Works

Systematically testing and tagging components ensures that only verified, high-quality materials enter your production lines. This upfront diligence prevents bigger headaches downstream, like failed batches or consumer complaints.

4) Poorly Enforced In-Process Checks

CGMP emphasizes in-process testing to ensure that each stage of production is proceeding correctly.

However, some companies skip or rush these checks, hoping final release testing alone will catch any issues.

That’s a dangerous gamble because end-stage testing won’t always reveal process-related problems.

Regulatory Basis

Written Procedures for Production and Process Control: The regulation says each batch must “have the identity, strength, quality, and purity they purport” to possess. You’re expected to follow pre-approved instructions at each manufacturing step, including specific sampling or testing intervals.

In-Process Materials: Whether it’s measuring weight variation for tablets or checking bioburden in non-sterile liquids, you need “appropriate control procedures” designed to prevent variability (ref. parts of § 211.110).

Practical Example

A topical cream manufacturer has an SOP specifying every 1,000 jars, and an operator checks viscosity to confirm uniform mixing.

Under production pressure, operators only test once at the start and once at the end.

If a mixing blade malfunctions midway, jars produced during that gap might differ in consistency or efficacy – yet no one notices until consumers complain.

Solutions

Embed In-Process Testing in SOPs: Spell out sampling frequency (“every X minutes or Y units”), acceptance criteria, and operators' actions if results are off.

Immediate Documentation: Record each in-process result in real time. If you wait hours, data can be “filled in” from memory or guesswork, raising compliance concerns.

Link Changes to Revalidation: If you alter mixing speeds, blend times, or temperature parameters, confirm you can still meet in-process specs.

Why It Works

Consistent in-process checks let you spot and correct deviations early, reducing product loss and guaranteeing uniform batches.

This also satisfies the regulation’s requirement to monitor critical phases, preventing substandard goods from reaching consumers.

5) Neglecting Facility and Equipment Standards

21 CFR Part 211 expects you to maintain suitable buildings and equipment to avoid cross-contamination, ensure proper sanitation, and maintain robust ventilation.

If your facility is cramped, poorly lit, or equipment cleaning schedules are seldom updated, you risk major compliance violations.

Regulatory Basis

Buildings and Facilities: The regulation highlights the need for adequate space to “prevent mixups” and “facilitate cleaning, maintenance, and proper operations.” Aseptic processing demands smooth, easily cleanable surfaces, filtered air, and environmental monitoring.

Equipment Construction and Maintenance: Surfaces in contact with drug products must not be reactive or shed contaminants. Written cleaning procedures are mandatory, along with logs showing who cleaned what and when.

Practical Example

A penicillin manufacturer attempts to produce a non-penicillin antibiotic in the same building – without fully separated air systems or dust controls.

Later, trace penicillin contamination is found in the antibiotic, prompting a swift FDA citation because mixing penicillin with other drug lines is specifically regulated.

Solutions

Dedicated Areas: Separate or define areas for quarantined goods, packaging materials, rejects, and different product families. This is crucial if penicillin is involved.

Written Sanitation and Maintenance Schedules: Outline how often floors, walls, and equipment are cleaned, which agents you use, and how you record completion.

Environmental Monitoring: If you produce sterile or high-sensitivity drugs, run routine air particle counts and microbial swabs to confirm compliance.

Why It Works

Proper building layout and equipment upkeep help you avoid cross-contamination or adulteration, thus meeting the fundamental CGMP principle of consistent, contaminant-free production.

6) Mishandling Returned, Rejected, or Salvaged Products

When returned drug products come back from the field (maybe due to shipping errors or consumer complaints), some manufacturers hastily re-label or re-blend them with fresh stock. Others salvage goods that were exposed to harsh conditions (e.g., floods, fires) without thorough testing.

Regulatory Basis

Returned Drug Products: The regulation states that if there’s any doubt about how a product was stored or shipped, that item “shall be destroyed” unless tests prove it’s still safe and intact.

Salvaging After Accidents: If products face extremes (temperature, humidity, smoke, etc.), you can salvage them only after “evidence from laboratory tests and assays” confirms they meet all standards of identity, strength, quality, and purity.

Practical Example

A distribution error sends a pallet of syrups to a remote warehouse for months without temperature control.

They come back to the manufacturing site with possible microbial contamination.

If you simply re-box them for sale, ignoring thorough retesting, you’re risking consumer health and an immediate FDA violation.

Solutions

Hold and Investigate: Quarantine every returned lot. Document the reason for return, location, or shipping conditions, and do lab checks as needed.

Adequate Tests for Reprocessing: If you must reprocess, outline each step in writing: what new controls ensure it meets original specs?

Destroy or Document: If safety or purity are in doubt, the regulation strongly suggests destroying the product to avoid risk.

Why It Works

Clear SOPs for handling returns or salvaging ensure questionable products don’t re-enter commerce. This protects patients and meets the regulation’s standard that all batches must conform to labeled specifications.

Further Strategies for Smooth Compliance With FDA 21 CFR Part 211

Given these pitfalls, how can you fortify your operations against them? Below are some strategies to consider:

Practical Example: Putting It All Together

Let’s consider a hypothetical scenario:

Company A makes oral solid dosage forms (tablets) using outsourced excipients. They have a QCU on paper, but that unit rarely rejects materials.

Their production line seldom performs in-process tablet weight checks, and they rely fully on the final “blend uniformity test.”

They also store “approved” and “unapproved” excipient drums in the same area due to space constraints.

What Goes Wrong?

A supplier’s excipient lot has variable particle size not caught by any in-house identity test.

During mixing, uniformity is off, but because in-process checks are skipped, nobody notices.

Final tablets fail dissolution tests, but by then, thousands are produced.

Attempting to salvage some tablets, the firm runs partial re-blending with a fresh excipient, contrary to the original SOP.

Result:

FDA inspection uncovers incomplete documentation for re-blending, no real-time batch data, a powerless QCU, and co-mingled raw materials.

The facility receives a warning letter citing specific references to 21 CFR Part 211 (lack of identity testing on each component lot, missing or inaccurate production records, unvalidated rework procedure, and insufficient QC oversight).

Rescue Plan:

Company A invests in an eQMS (electronic Quality Management System) that enforces quarantine status for each excipient lot. Operators must scan barcodes before usage, preventing accidental use of unapproved lots.

They revamp in-process checks with a standard schedule (e.g., weigh 20 tablets every 30 minutes). Results are recorded immediately on digital forms, each time referencing the specific batch.

The QCU receives additional staffing and a dedicated lab area for routine identity tests on incoming excipients, as the regulation demands.

All re-blending or reprocessing steps go through a documented approval process to show compliance with 21 CFR Part 211 standards.

By aligning each fix with the letter and spirit of 21 CFR Part 211, Company A gets back on track, steadily restoring trust among regulators and customers.

Elevate Your FDA 21 CFR Part 211 Compliance With Signify

As seen in Company A’s journey, transforming a reactive and disjointed system into a proactive, well-documented, and transparent process can rapidly turn non-compliance around.

Investing in real-time monitoring, quality checks, and an empowered Quality Control Unit meets the minimums of 21 CFR Part 211 and fosters a culture of excellence for regulators and customers to appreciate.

Signify offers a modern, comprehensive platform that simplifies this transformation:

Continuous Compliance: Leverage AI-generated smart checklists to spot issues in SOPs, packaging labels, or raw material documentation before they escalate.

Automated Evidence Traceability: Instantly locate and reference critical sections in your quality records, enhancing transparency and speeding up audits.

Real-Time Risk Monitoring: Conduct on-the-fly conformity assessments, automatically detect changes in regulations, and stay informed of internal document updates that might introduce nonconformities.

By integrating Signify into your operations, you gain the agility to adapt to evolving regulations, pinpoint and address compliance gaps, and demonstrate unwavering adherence to 21 CFR Part 211.

Ready to modernize your compliance strategy?

Schedule a demo and explore how Signify can streamline your regulatory and quality workflows.

The information presented is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, regulatory, or professional advice. Organizations should consult with qualified legal and compliance professionals for guidance specific to their circumstances.

21-CFR Part 211 - Guidelines for Pharmaceuticals

21-CFR Part 211 - Guidelines for Pharmaceuticals

Feb 12, 2025